While held at a Chinese labor camp, Henry Yue was forced to wind metal coils used in television sets, day in and day out. The grueling conditions were such that blood would sometimes gush out from Yue’s nose, leaving large crimson patches on his blue-and-white striped prison uniform.

The first time it happened, Yue held up his head and patted his forehead for about a minute to stop the bleeding. There was so much blood that even on the second day he was coughing it out.

Yue was at a facility in eastern China’s Tianjin city serving a 1.5-year sentence in 2001 as a punishment for doing Falun Gong’s meditative exercises during a “brainwashing” session, a program mandated by the communist regime designed to coerce adherents of the spiritual practice to renounce their faith.

The young professional didn’t think his health would decline to such a point. He was in his mid-20s, athletic, and in excellent health before imprisonment. But every aspect of prison camp life took a toll.

He was forced to toil 16 to 19 hours each day with the only sustenance being moldy rice and stale greens; he had to shower in cold water even during frigid winters; every day he had to report about how his thoughts have been “transformed”—a euphemism coined by Chinese authorities for an adherent renouncing their belief.

The guards would inflict pain on them for the slightest sign of disobedience, or even no reason at all. Once, he watched a senior warden, for no reason, smash a chair to pieces on an inmate’s hunched back.

The labor camp would set impossibly high production quotas for each detainee, often leaving little room for rest. Yue, who was one of the fastest workers there, remembered having once slept for only half an hour in trying to finish his quota.

To get by, he would often countdown by the minute for the ordeals to end. It eventually did, but only after he slaved for 18 months on these products that would later be sold in South Korea. Still, he considered himself among the lucky ones: there were others who had deformed hands or lost their fingernails because of the work.

“They treat you like animals,” Yue, who now lives in New York, told The Epoch Times. He cited an infamous order from the then-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Jiang Zemin, which essentially gave free rein to torturers to use any means possible to get adherents like him to give up their spiritual belief. Jiang orchestrated the persecution of Falun Gong in July 1999.

“Ruin their reputations, bankrupt them financially, and destroy them physically,” Jiang had said at the onset of the nationwide suppression, envisioning that he could eradicate Falun Gong in just three months. While this didn’t come true, the persecution turned an estimated 70 million to 100 million in the Falun Gong community into targets of an uninhibited elimination campaign, involving, but not limited to, detention, torture, financial deprivation, hate propaganda, and forced organ harvesting.

A ‘Horrific Era’

Jiang died on Nov. 30, at the age of 96, with his legacy described as one of the world’s worst human rights abusers.

But so long as the persecution apparatus Jiang created remains in effect, accounts of suffering like Yue’s and the overarching climate of terror endured by Falun Gong adherents for the past 23 years are unlikely to end.

Between September and October, more than 2,000 adherents experienced harassment or arrests, including about 150 who were 80 years or older, according to Minghui.org, a U.S.-based website that serves as a clearinghouse for the persecution. Yet those figures represent the tip of the iceberg in the decadeslong campaign that has seen millions of adherents detained, and an untold number who have died from torture or forced organ harvesting.

“To some extent, it’s the end of a very terrible, horrific era,” Levi Browde, executive director of the New York-based Falun Dafa Information Center, told The Epoch Times.

With Jiang, the mastermind who elevated a “mafia” ring of acolytes to execute the persecution, now gone, Browde hopes that anyone “who still has somewhat of a conscience” would stop contributing to the mass abuses.

Millions Impacted

Falun Gong features moral teachings rooted in the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, along with a set of meditative exercises. Its popularity surged soon after being introduced to the public in 1992, spreading by word of mouth to nearly one in 13 Chinese, many of whom said they benefited from the practice physically and mentally.

But such meteoric growth was perceived by Jiang as a threat to his and the Party’s authoritarian control over the country.

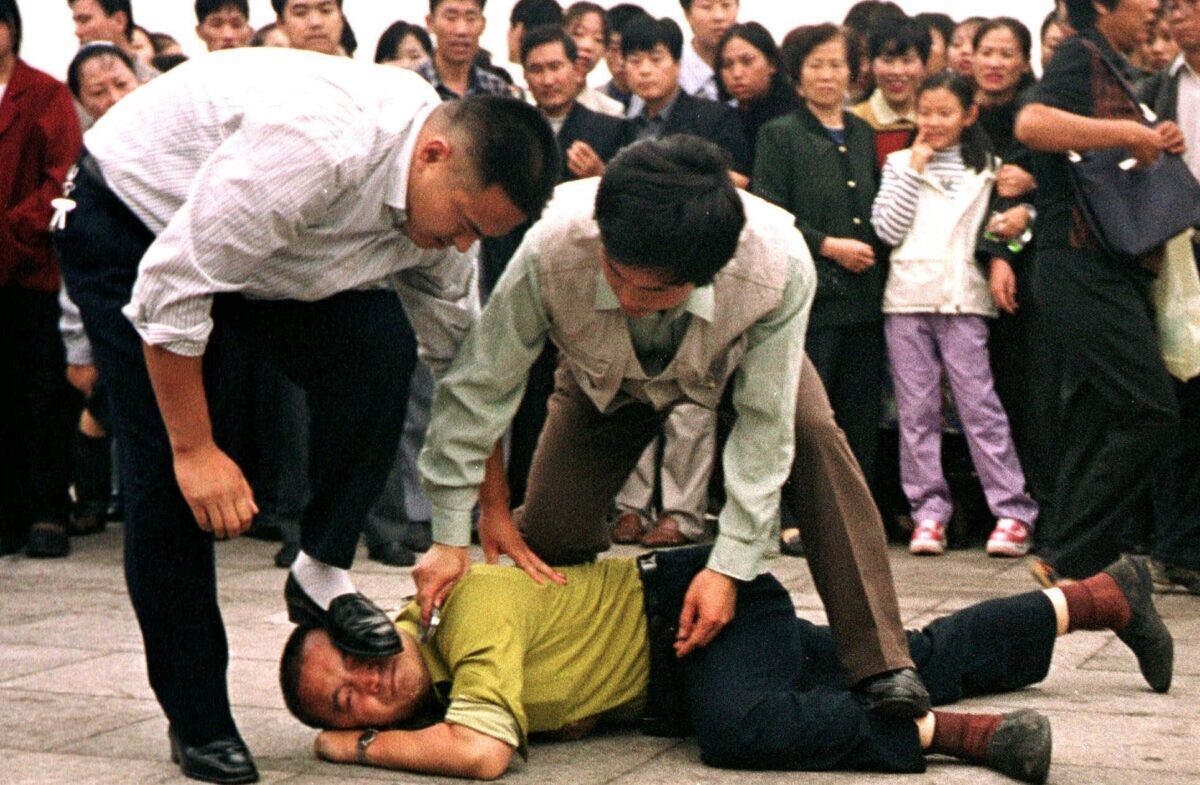

In June 1999, the then-leader created an extra-legal police task force that became known as the “610 Office,” with the sole mission to annihilate Falun Gong. A national campaign was launched a month later. Hate propaganda filled the airwaves, print media, and community bulletin boards, as police assembled en masse to make arrests.

Everything—family, career, and even their own lives—was at risk for those who persisted in their belief, even though adherents argued that they were merely exercising their basic rights enshrined in China’s constitution.

Young as he was, Yue was already moderately well-off as a junior manager at a Japanese joint venture that manufactured children’s clothing, taking a salary of up to 1,000 yuan ($142) a month, which placed him among the top earners at the time in his town in Tianjin, a major coastal city in China’s north.

That financial cushion was stripped from him that October after Yue went to Tiananmen Square in the country’s capital to petition authorities to reverse their decision.

After he came back to Tianjin, local police officers arrested him and tortured him with two electric batons for 40 minutes, stopping only after one of them accidentally shocked himself and screamed.

It was then that Yue, who had always looked up to the police force as heroes who helped make people safe, sank into despair.

“Facing a group who only wanted to better themselves, they could still be so ruthless,” he said. “They were persecuting good people under the authority of the state.”

West’s Greenlight

Browde, then a software engineer in New York, took up the spiritual practice in the fall of 1998 after noticing how it changed his best friend and coworker into a kinder and more considerate person. Soon, the slow-motion exercises replaced his hour-long gym routine every morning.

The practice, he said, pointed the way to allow one to “be the person you want to be” in a world where often “the various complexities of human nature get the best of us.”

“I find that very freeing,” he said.

It wasn’t long after the persecution that the same friend who introduced him to the practice found that his mother in China, also an adherent, was missing, an event that brought the persecution close to home.

Browde and others formed a small group to go door-knocking to tell Americans about what was happening in China. He traveled to protest during several of Jiang’s overseas visits, in Ukraine, Lithuania, and the two U.S. trips in 2000 and 2002.

At the time it felt as if Browde and others raising awareness about Falun Gong’s plight were “swimming against the tide,” he recalled.

The West, having just welcomed China into the World Trade Organization the previous winter, was “desperate” to bring the communist country into the world political arena—even at the cost of their values and legal principles—and the Chinese officials knew it, said Browde.

He recalled a run-in with two Chinese officials in October 2002, during a demonstration ahead of Jiang’s meeting with then-President Goerge W. Bush in Crawford, Texas. Bush was set to give Jiang a tour around his ranch, which Browde described as a “huge PR coup for the CCP on the world stage.”

“This was normalizing the CCP in showing that it was an equal to the United States, not just politically and financially,” he said.

“So we felt it was our duty that we had every chance possible to make sure that people understood that this person coming to visit with our president here in Texas was a tyrant.”

As he and hundreds of other adherents gathered on the road leading to the ranch, two officials from a Chinese consulate car came out and started to take photos of the participants. When the adherents objected, out of safety concerns due to participants having family in China, one of the officials fetched a Stetson cowboy hat from the car, put it on, and walked towards them with his arms folded.

The message, as Browde saw it, was that “you can’t do anything to me.”

“That’s one of the moments where I first realized that the Chinese officials were succeeding at getting their way to do what they want in our country,” he said.

Turning Tide

That was more than 20 years ago, and the tide has shifted since then.

The Chinese regime’s state-sanctioned forced organ harvesting from imprisoned Falun Gong adherents is seeing growing condemnation in the United States and around the globe.

Meanwhile, over the past few years, the regime’s threatening overtures against Taiwan, its mass imprisonment of Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang region, its suppression of Hong Kong, and its harsh COVID measures on the Chinese population at large have also sparked significant backlash in China and abroad.

Following Jiang’s death, Chinese state media was awash with eulogies lionizing the former leader. In an official obituary, the Party, without mentioning the specific incident, credited Jiang for taking a hardline stance during the 1989 Tiananmen protests which called for political reform.

While this came as no surprise to adherents, the praise from some Western media outlets over Jiang’s alleged role in facilitating the country’s economic rise was.

Such characterizations amounted to a whitewashing of Jiang’s bloody legacy, according to Yue.

Not only did the former leader unleash the full force of the state against a massive group of innocents, but his rule also spawned the endemic corruption that now permeates every aspect of Chinese society, Yue said.

In 2015, Yue, who in total was arrested half a dozen times, was one of the first in his county to file a lawsuit using their real name with China’s highest legal body asking Jiang to be brought to justice. In about a year and a half, the number of similar lawsuits filed against the former leader over harms suffered due to the persecution snowballed to about 210,000.

While at the labor camp, Yue had once wished Jiang dead, although his resentment had long since dissipated.

“We don’t have enemies,” he said.

Yue, however, does he regret that now he won’t be able to see Jiang stand trial for his crimes.

He also questioned whether the Chinese public held much warm sentiment toward Jiang. In 2011, rumors of Jiang’s death circulating in Hong Kong had reportedly prompted some in China to buy fireworks in celebration.

“For them, it was something they had looked forward to,” said Yue.

Jiang’s death has added political uncertainties to Beijing as it faces challenges both domestically and abroad.

Browde saw the anti-lockdown protests that recently erupted across China as part of a growing pattern of Chinese people “being more clear” about the regime’s history and abuses.

This awareness, he said, has been growing for years, in part thanks to adherents’ grassroots efforts to tell people about the persecution.

In recent years, his organization has collected acts of courage of various scales, including entire villages signing petitions using their real names to call for release of detained Falun Gong practitioners.

“That’s unprecedented— a bunch of people signing their real names to a petition and sending them to the government on an issue that the CCP takes so seriously like Falun Gong,” he said.

“So if they’re brave enough to do that, they should be brave enough to do other things such as say no to COVID lockdowns,” Browde added.

“At some point that would hit a tipping point.”

Frank Fang contributed to this report.