The rescue of Cleo Smith made global headlines.

The four-year-old vanished from a tent in the middle of the night on a family holiday, sparking an 18-day search involving more than 100 police officers and thousands of volunteers.

She was recovered alive and well in the locked room of a house in the small coastal town of Carnarvon, just minutes from her home, on Wednesday.

The Australian prime minister called it a miracle. Police officers, from the Western Australia police commissioner down, admitted to openly weeping.

The Western Australian premier, Mark McGowan, travelled 900km from Perth to see the four-year-old and her family, presenting her with two teddy bears in police uniform that he had named after two senior detectives who worked on the case.

On the morning she was found, talkback radio in Perth lit up with callers who admitted crying at the news, their relief and joy overwhelming.

It was a very good news story.

Most missing person cases do not run like this. And if the person who goes missing is Indigenous, sometimes there is no report at all.

It is not surprising that Cleo Smith’s disappearance and rescue captured worldwide attention, says Dr Sarah Wayland.

Waking up to discover your child gone is every parent’s worst nightmare. To recover that child again after thousands of hours of dedicated police work, finding her safe and well in her home town, allegedly taken by a man who has no connection to her family, sounds like the final act of a movie.

It’s the least common type of missing person case – just 0.6% of the almost 40,000 missing person reports in Australia each year relate to an abduction – and an even more rare happy ending. Of course the world was hooked.

“There’s a cute little girl, we can imagine what it would be like to have lost her and we can also imagine how vulnerable she is because of her age so we can connect with it,” says Wayland, who has almost 20 years experience working with the families of missing persons. “The case of her being found proves that the world can offer us a problem, that we throw resources at it and that it gets fixed. That it neatly ties itself up.”

That Cleo disappeared from a campground 75km north of Carnarvon on the Western Australian coast created, for international audiences, a layer of outback mystique — what Wayland calls the Picnic at Hanging Rock effect.

“It buys into the mysticism and intrigue and romanticism of Australia and its wildness and how people can vanish without a trace from these locations,” she says. “These narratives already exist in people’s heads. The real facts of the case can connect with the story that’s already there.”

In the UK, some media outlets dubbed Cleo “Australia’s Madeleine McCann”, in reference to the three-year-old British child who was taken from her bed on a family holiday in Portugal in 2007.

These narratives help grow public attention, which is a crucial part of a missing person investigation. But the story can overtake the facts, and those following closely, who have become invested in the characters, may have difficulty stepping back and respecting the missing person’s privacy once they have been found.

“You invite people in because the family’s ultimate goal when someone is missing is to do anything they can to bring that person home,” Wayland says. “But once you’ve been able to reach a resolution, whether it be a positive resolution or not, you can’t just say, ‘thanks very much we’re going to pack up our things and go home now’.”

In the case of Cleo Smith, it is the police that have kept feeding the story post-rescue, releasing audio of the moment of the little girl’s rescue and video of her a few minutes later. On Friday night, police distributed a statement from the family who thanked everyone involved in the rescue and asked for their privacy to be respected.

Her successful recovery appeared to bolster morale inside the police force and its public reputation, both of which were at a low ebb.

Linda Cao, a former senior lawyer with the Aboriginal Family Legal Service, watched events unfold with a sense of relief for Cleo’s family and disbelief that the same police force that had at times refused to help her clients were being hailed as heroes.

“Thank goodness you did the job well and there was a good outcome, but you should be doing this with every case all the time,” Cao said. “Regardless of what the outcome is, the effort should be the same.”

Cao says she has at times been unable to get police to investigate reports of a missing child, because the parent who reported them missing had been declared unfit by child protection authorities. In some parts of regional WA, she says, the disappearance of children and young people is so pervasive that “to police it’s just their normal”.

One case involved a 13-year-old girl who ran away after being removed by police from her mother into her father’s care, despite her mother being awarded custody by the family court. Her mother’s attempts to report her missing failed. The girl was later found living with a middle-aged man and had become addicted to illicit substances which she was provided in exchange for sex. A local police officer told Cao they would not intervene as the child was there by choice.

“The police say that’s just what happens out here,” she says. “If the police will not get involved, who else is there? There is nobody else.”

Sometimes First Nations communities undertake the search themselves. Watching reports of Cleo’s rescue, Bundjalung woman and advocate Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts, who was forcibly removed from her family at the age of 11 and placed into state care, said she felt relieved for her family and community and sorry for those families whose loved ones remain missing, and who are still fighting for police and public attention.

“We have had so many of our kids just recently go missing and it’s up to community to start those GoFundMe pages, it’s up to us to demand to the coroner, to the courts, please give us some more time, can you please help us,” Turnbull-Roberts says. “But when it’s a non-Indigenous child there’s all these resources, families and communities don’t have to think twice about whether the courts are going to respond, about whether police are going to stop their investigation.”

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are disproportionately represented in missing person reports, many of which concern children who have been removed from their families by child protection orders.

A review by the Victorian commissioner for children and young people found that children in care were reported missing at 75 times the rate of other children in the same age cohort.

Another review prepared for the Australian federal police in 2021 found that at least 25.6% of children under 12 and 18% of those aged between 13 and 17 who go missing while in care are Indigenous, despite First Nations children making up just 5.9% of the total population under 18.

“You don’t see that same response for First Nations children,” Turnbull-Roberts says. “So many people say it’s not an issue of race but it becomes an issue of race when the level of response isn’t equal.”

Those stories are not frequently told in the media because of legal restrictions around reporting on child protection cases, and also because they are complicated, often contain conflicting accounts, and are overshadowed by opaque and unhelpful government departments.

“When you have stories of children that go missing because of another individual, there is a sense that the state (through police) is the saviour,” says Prof Thalia Anthony, an expert on the policing and criminalisation of Indigenous peoples with the University of Technology Sydney. “But with Aboriginal kids in care it is the state that has failed in its role as protector.”

In Cleo’s disappearance, “the police are the good guys. They don’t have that same role when Aboriginal kids go missing”.

There is often an assumption that the family is to blame, or that a child has left by choice, Anthony says. Families are evaluated, by police, by the media, by the public, to see if they “deserve” the help.

The day before Cleo was found, the family of Aboriginal man Andrick Ross, who has been missing since 28 September, made a public plea for assistance to help find him. The 35-year-old artist’s car has been found in outback Queensland, near the Northern Territory border. On Thursday the family of an Aboriginal man from the East Kimberley, Jeremiah Rivers, issued a similar plea. He was last seen on 18 October.

The family of another young Aboriginal boy, who went missing in the Kimberley in December last year, have requested his name and image no longer be used. He is still officially listed as missing by WA police but there are no active search efforts.

Earlier this year 250 people marched through the NSW town of Moree to demand answers over the disappearance of a 22-year-old Gomeroi man, Gordon Copeland, last seen running from police on 10 July. His remains were found last month.

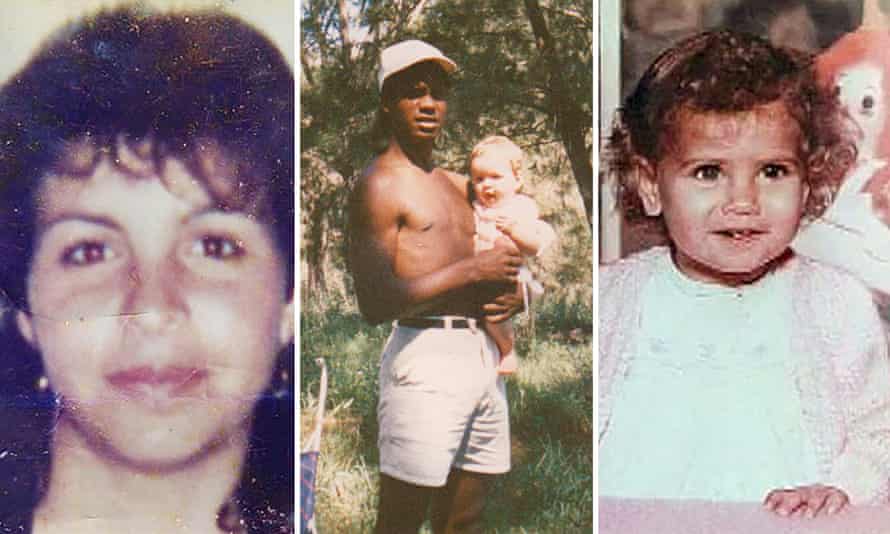

The families of the Bowraville children fought for three decades for a proper investigation into their disappearance, which finally resulted in murder charges.

“We see it as a community,” Turnbull-Roberts says. “I don’t think white Australia sees it. But we see it.”