In 1998, in a hilarious work called Diary of a Victorian Dandy, Yinka Shonibare inserted himself, impeccably attired, into the sitting rooms, drawing rooms, billiards rooms and bedrooms of high society Victorian Britain, invariably causing a sensation in each of the perfectly mocked-up photographs. The work mimics William Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress, but instead of ending up in Bedlam, like Hogarth’s protagonist, Shonibare the Dandy triumphs over white society at everything from financial dealing to fine conversation. It all climaxes with him having a great time in a brothel with no apparent guilt or punishment. Well, it was the 1990s – and Shonibare was a bona fide Young British Artist. Also, he says with a laugh, “Hogarth was the first YBA.”

Shonibare has played plenty of games with art and history since, including refitting a model of HMS Victory – that most British of all vessels, the flagship of the Battle of Trafalgar – with sails of (supposedly) African batik fabric and sticking it in a giant bottle. But now the British-Nigerian artist is turning his attention to the birth of modern art in Picasso’s Paris. Not many artists come away from an encounter with Pablo looking good. A 2012 Tate exhibition about the Spaniard and modern British art left Henry Moore and Francis Bacon looking very small indeed. But Shonibare engages with the old Minotaur in a relaxed, funny yet profoundly insightful way.

“After Matisse showed Picasso African art for the first time,” he says, “it changed the history of modern art.” This is no hyperbole. It immediately led Picasso to repaint Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the incendiary canvas he was working on in his ramshackle Montmartre studio, giving three of the five naked sex workers in it “African” masks that set them free from all previous western artistic values and rewrote the rule book about what an image can be.

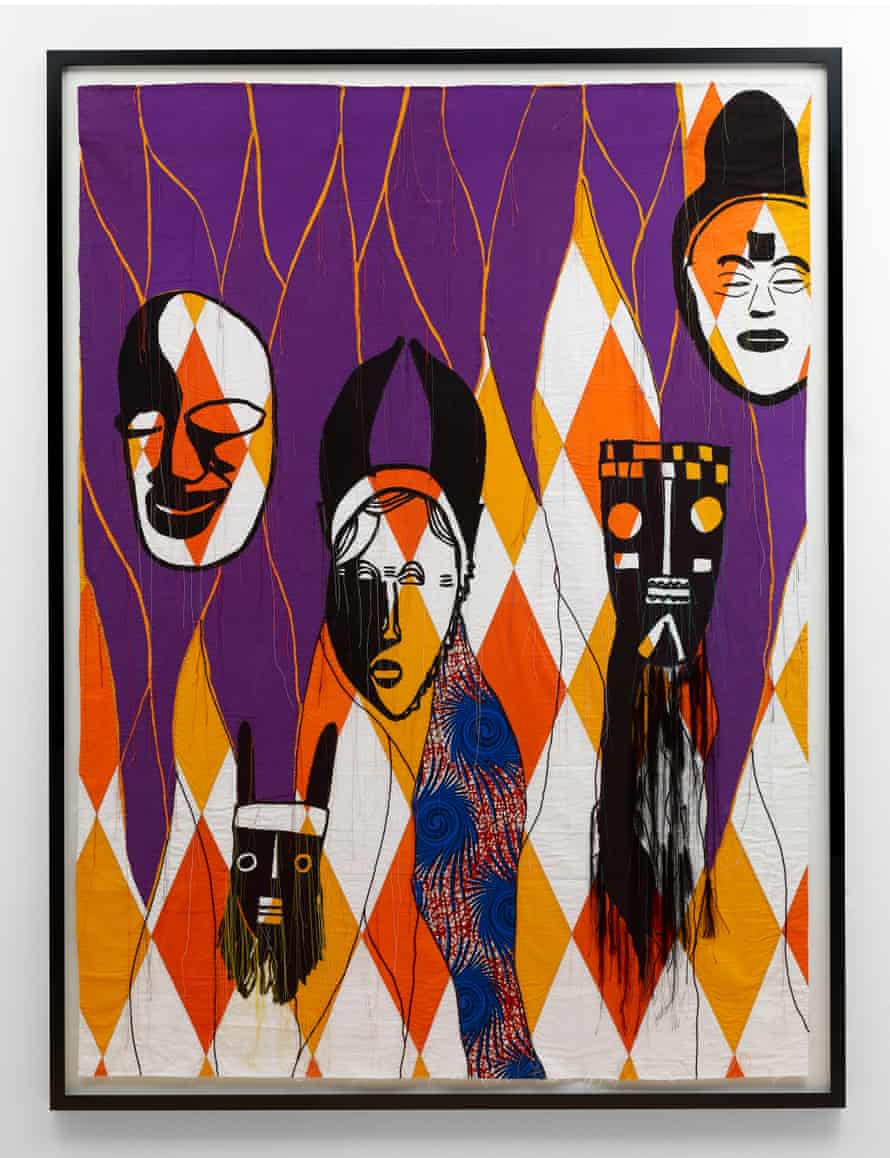

More than a century on, Shonibare is returning to this seismic shift in his new exhibition, African Spirits of Modernism. Three statues at the beginning of the show, at the Stephen Friedman gallery in London, mix animal and human anatomies, as well as European and African traditions, revisiting that tumultuous moment in Paris in a dazzling way. An African mask, showing a human head with animal horns, floats on top of a decapitated Greco-Roman statue of a centaur. It’s covered in the batik fabric patterns that Shonibare calls “my trademark”. More African masks are appended to classical European statues of a sphinx and the goat-legged god Pan. All are replicas of masks Picasso owned.

Among many other things, Shonibare reveals the sheer scale of Picasso’s collection of African masks. This is acutely apposite, at a time when museums are being hit with demands to return “cultural property” to wherever it originated. But Shonibare’s aim is not to attack Picasso. “When I looked deeper, I saw Picasso was genuinely fascinated by the spiritual power of these objects – it wasn’t just decoration. He went for sculptures that were frightening: half-animal, half-human.”

So this is not a critique of cultural appropriation. “I’m not one of these people who challenge cultural appropriation in that way,” he says. “Of course, I recognise power issues. I recognise that the dominant culture can misuse something.” But Shonibare delights in the exchanges, crossovers and ironies that can ensue. He uses batik patterns because they suggest authentic African-ness, yet they were first sold in Africa by the Dutch in the 19th century and are actually derived from Indonesia.

He sees a parallel with the new show. “It is a celebration of the works of my ancestors,” he says. “But there’s also the irony that a contemporary African encounters this spirituality through the eyes of modernism, through the eyes of western art, because I’m distant from the works of my ancestors – they’re not something I’ve used myself, in rituals or in initiation ceremonies as they did. The west created this hybrid monster which is myself.”

There’s no doubting the imperialist context of Picasso’s African art encounter, however. France’s colonies at the beginning of the 20th century included Ivory Coast, Dahomey, Niger, French Sudan, Senegal and elsewhere. Artefacts from these lands were displayed in Paris in the notoriously shabby galleries of the Musée du Trocadéro. Picasso, suggests Shonibare, was unique for his time, showing an intuition for the religious depth and ritual purpose of these objects whose anonymous makers he never met.

“I think what came after,” says Shonibare, “became more like decoration or fashion. I don’t believe other artists were looking with the same depth.” With Picasso leading the way, modernist Paris went crazy for Africa – or rather a fantasy of Africa. “The French were very interested in these cultures,” says the 58-year-old artist. “But then there is another side: the exoticisation, the fetishisation. It’s a two-way thing, though.”

Black artists, he points out, “mimic the stereotype. Josephine Baker does the banana dance, pretending she’s from Haiti. But she’s not from Haiti, she’s American. Economically, it’s actually profitable to be as exotic as possible.”

There is, however, another reason why Shonibare has chosen to investigate the modernist age now: he wonders whether today’s art world is having a similar moment of exoticism. “You’ve got Black Lives Matter, people fighting for social justice. Then you have an explosion in the market of black art becoming really fashionable, but not with any distance or critical thought or trying to understand these things in a deeper way. Every young artist is trying to paint like Kerry James Marshall [an acclaimed painter of black American scenes], because that’s where the market is. So is this genuine empowerment for artists of African origin? Is this going to last? Or is this another Harlem renaissance that’s just going to be yesterday’s fashion?”

Shonibare is not offering simple answers, just posing difficult questions. “If you look at the western art market, I think 2% is the work of black artists maybe – a tiny proportion. So there is no proper equilibrium yet. There’s only fad and fashion, no serious depth to the collecting. Overpriced auctions of one or two artists don’t solve the problem.

“Picasso was radical. I wish more contemporary artists would be brave enough to not follow the crowd. I have a lot of respect for Picasso. Disruption is something I value – and I identify that disruption in Picasso’s work. We’re so used to those works now, they’ve almost become like classical art. But can you imagine what they would have been like at the time?”

Surely, though, there’s an injustice built into the legacy of the modernists? African creativity played a huge part in releasing the west from dead traditions and ushering in modernity with all its freedoms. What did the makers of those world-changing masks get in return? It’s an idea Shonibare runs with: “Things haven’t changed that much for people of African origin. You’ve had the whole kind of modernist temple, so-called high art, built on the back of the art of Africa. But that’s never really confronted and acknowledged. Modernism is a very individualistic, self-centred type of culture.”

So it shouldn’t be acceptable to celebrate the genius of Picasso without fully acknowledging the genius of the cultures that inspired him: we are who we are partly because of the masks that are born again in Shonibare’s magical show. As for African artistic masterpieces, now they’ve given so much to the west, does he think they should be returned? Do the Benin sculptures in the British Museum, looted in 1897, belong back in Nigeria?

“I think that it’s a matter of respecting people and their heritage. The British Museum can have replicas of these objects: they don’t have to be here. I think a symbolic gesture should be made. We can’t carry on like the world has not changed. In Nigeria, they are building a museum and British people should be able to go there to understand those objects in the right context.”

He’s doing his bit to open up such encounters. “I’m building an artists’ residency space in Lagos, Nigeria. Artists will be able to go for three months. The building is nearly finished. Then two hours from Lagos we have a 54-acre farm and we’re practising sustainable agriculture. Artists will also be able to go to the farm to work.”

He thinks statues of slavers, such as Bristol’s monument to Edward Colston, should go if local communities want them to – or if not, then some historical context should be added. But he’d never make a “didactic” statue to replace such a work, as this would smack of “Soviet Russia”. And for this artist of humour, sensuality and irony, art is so much more than a set of good intentions.

“I keep talking about aesthetics,” he says, “because many people, when they talk about the work of black artists, focus on ‘the message’. They’re looking for a message.” Instead, he prefers to layer his art with beautiful fabrics, fancy rococo wigs and rich references. “I enjoy all of that and deliberately go over the top with it. White artists don’t have a monopoly on aesthetics.”