EXCLUSIVE: Yolanda McClary is setting the record straight on the “‘CSI’ effect” that has permeated the industry of crime scene investigating since the inception of the wildly successful series “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” in October 2000.

The renowned forensic specialist, who specializes in the recovery of DNA evidence and genealogy, admittedly has seen some things that have made her queasy in her decades-long career. But despite forging a career by discovering the unknown, McClary is now using her knowledge and experience to seek justice for women who have been forgotten in “The Jane Doe Murders.”

The one-time, two-hour special comes to Oxygen on January 3 and follows McClary and her team of genealogists, who aid local law enforcement in exploring an Oregon murder case from more than two decades ago.

McClary dished on the biggest misconceptions she says have come since the arrival of “CSI” and its countless spinoffs, and told Fox News why “The Jane Doe Murders” is unlike any other true-crime series before it.

“One of the key points is we start off with someone who’s unknown and there’s a whole different emotional level, I believe, when you’re working with Jane Does,” McClary said of her investigation into the special case.

“First of all, let’s look at the fact that they were someone that was murdered, discarded like trash, had their name taken away from them — family, never knowing what happened to them for years,” she said. “And even if you’re estranged from your family, you’re still somebody’s daughter — possibly somebody’s mother or sister. And there’s always somebody out there wondering, ‘Where are you? What happened to you?'”

McClary, a former Las Vegas crime scene investigator who communicated firsthand with the original producers behind the Sin City-based “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation,” said “The Jane Doe Murders” is unique in the sense that, “Yes, it is a cold case murder like many shows, but we do not know who she is.

“So the first thing we do is work the whole DNA process, which me being a crime girl, I love evidence and DNA is evidence.”

Once we figure out who she is, well, now all these roads open and you have to realize the police have never been able to really go down an investigation on this person because they didn’t know who she was.

According to Oxygen, “there are nearly 40,000 open cases in which the victim of a violent crime remains unidentified and loved ones are never returned to their families. These victims are called Jane or John Doe, and they become cold cases.”

McClary said she and her team worked the whole DNA gamut in their quest to solve the Jane Doe murder featured in the Oxygen special and “developed a profile on her that can be used in genealogy, which is really a whole different beast.”

McClary, who also holds credits on “The DNA Murder” and “Cold Justice,” credited her skills to her time working and learning under “top end people in genealogy” and believes with the huge leaps in technology, their case will be solved.

“They’ve taught me so much. It’s fascinating how that world works. And so ultimately our hope is that we can figure out who she is,” McClary explained. “Once we figure out who she is, well, now all these roads open and you have to realize the police have never been able to really go down an investigation on this person because they didn’t know who she was. The most they could do is try to figure out how she got there, does she have any evidence that could lead to a suspect who maybe dumped her there, which typically steers you into a big wall.”

“And so once you find out who your Doe is, well, now the whole investigation just opens up because now you can start backtracking — ‘Who was she? Where was she born? Who is her family? Was she married? Did she have kids? Who did she have for enemies?’ And this is something that no other true crime show out there has done.”

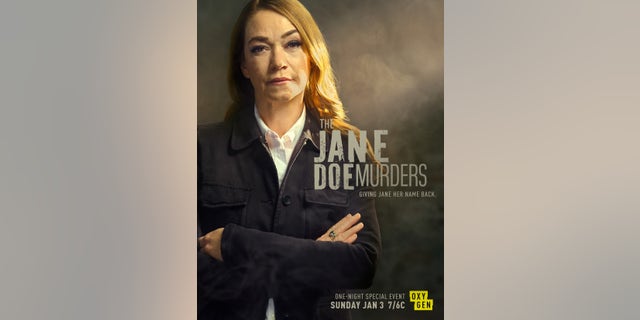

‘The Jane Doe Murders’ star Yolanda McClary debunked many misconceptions about forensic investigating brought on by the success of ‘CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.’

(Oxygen)

In today’s climate, McClary has no shortage of DNA database and forensic technology at her disposal – but the real-life crime scene investigator recalled the dog days when such wasn’t the case and technology wasn’t as mature.

She said the development of “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” shed a brand new light on her business for the betterment, but also created a sense that cases could be solved with the flip of a switch.

NEW EVIDENCE, TESTIMONY ABOUT MARILYN MONROE’S DEATH TO BE FEATURED IN UPCOMING DOCUSERIES

“You’re exactly right. You know, when the ‘CSI’ show came out, the writers and the different people trying to make all that happen for the episodes, they would reach out to us a lot and I really feel that they try to make some of the equipment they used very factual — and it was,” McClary explained.

“It’s called a time thing, you know, like the fingerprint – I loved it,” she continued. “They would put the fingerprint in the machine, which is an AFIS (Automatic Fingerprint Identification System) machine. And they put it in there and AFIS starts doing all this really cool s–t. Well, in reality, it really didn’t do that cool stuff with the visual effects as it’s comparing all of the prints in the database. I mean, it’s a database, so it’s looking for these points but they made it super cool. And I said, ‘God, I wish ours had all those green lights and looked so cool like that.’”

McClary said point-blank the AFIS machine viewers came to know and love on the show “doesn’t do that and it takes hours.”

“And then it finally spits you back 10 possibilities. And the No. 1 person is who they feel is your top possibility – now you have to go get that person that it said could be it. You have to go pull their fingerprints.”

The process is tedious at best, McClary noted, given the fact that most people who would be looked at as potential suspects have 10 distinct fingerprints which must be compared to the single hit AFIS believes could be one from the suspect.

The former Las Vegas crime investigator explained how ‘CSI: Crime Scene Investigation’ was an industry game-changer

(Oxygen)

“You have these 10 individual prints to see, ‘Is it [the suspect]?’ and if not, then you have to move on to the next,” McClary said through laughter. “Well, when you do the math – 10×10 is a hundred fingerprints you are looking at that AFIS thinks is your best hit. A hundred. So they’re not making that easy.”

She added, “Sometimes it goes, ‘Bam, this is it,’ – love it. And yes, it was done in maybe four or five hours, OK, but it’s not usually how it works.”

Other misnomers McClary brought to the table were the fact that the “beautiful” crime scenes showcased on TV couldn’t be further from reality and said there had been many times in her career where she had gotten to a gruesome scene only to remove herself for a moment of clarity before returning to perform the task at hand.

“They make this really complex murder crime scene, which I was like, ‘Oh, I like the fact that they did this and there’s trajectory and blood spatter and all this cool s–t and OK, I love it – but they’re wrapped up in an hour while in reality, we’d be wrapped up like 17 hours later,” McClary explained.

“I mean, the actors playing the investigators always look beautiful when they’re done. We always look like s–t by the end of our shift,” she pressed. “They look nice enough to go and get a drink at a bar – yeah, no. We all look like just tattered, awful-looking people and we stink because half the time we might have been in a dumpster.”

But aside from the theater that scripted television provides, McClary said she appreciated the recognition and respect those in her industry have since coveted from the success of “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation,” and added that in her time, the number of people who inquired about getting into the business has skyrocketed through the years.

The actors playing the investigators [on ‘CSI’] always look beautiful when they’re done. We always look like s–t by the end of our shift.

“I think they did a great job on trying to portray what we did because, let me tell you, before the ‘CSI’ show, I would be on scenes and people would go, ‘Hey, camera girl – this is a crime scene, so I need you to back up past the tape,’ McClary recalled. “But after the ‘CSI’ show, they never said, ‘Hey, camera girl’ again. And, you know, I was happy about that. People actually knew what I did for a living.”

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR ENTERTAINMENT NEWSLETTER

She added the TV series brought a newfound respect for the profession as a whole, but almost to a detriment for prosecuting attorneys who had to fight juries that only wanted to see DNA associated with cases.

“It was great for us, CSIs – we were getting great publicity, which we never had before. You know, it’s always the detective that gets all the publicity,” McClary quipped. “And we were getting the publicity because they were showing what we really do on a daily basis.”

She maintained: “And, yes, it was great. But then there comes a ‘CSI effect,’ which was, every time they even had a burglary, anything. If there was nothing for us to do, the cops wouldn’t call us. The first thing people would say is, ‘Well, CSI is showing up and they’re bringing all that equipment, right?’ And it’s like, ‘Yeah, no, that’s not happening.’ And people also support the show because the show always got everything. They always got all the DNA. They always got beautiful fingerprints. And it doesn’t really work that way.”

In the real-world of investigating a crime scene, “sometimes there is no DNA to be had or we can’t get it for whatever reason,” McClary said. “Prints – a lot of times they’re smudged or not usable or the perpetrator wore gloves and they’re not there – so that was hard for people to grasp. So we called it the ‘CSI effect.’”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Ultimately, McClary looked at the exposure as a “double-edged sword.”

“On one hand, we finally were recognized for the work we did, which was amazing. But then there was the ‘CSI effect’ and it was hard for the district attorneys in the DA’s office when prosecuting because all the jury wanted to do was have a CSI get up there and, you know, pretty much tell them all the wonderful things that happened,” she said.

“And sometimes we could do that and sometimes we couldn’t. So it was a double-edged sword, but it’s OK. I think the double-edged sword still worked out for everyone.”

“The Jane Doe Murders” premieres Sunday, Jan. 3 at 7 p.m. ET/PT on Oxygen.