Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced he is running for president in a video posted to Twitter on May 24.

“I’m Ron DeSantis. And I’m running for president to lead our great American comeback,” DeSantis says in the short campaign launch video posted to Twitter minutes ahead of his Twitter Spaces conversation with one of the world’s richest men, Elon Musk.

“Our border is a disaster, crime infests our cities, federal government makes it harder for families to make ends meet, and the president flounders. But decline is a choice. Success is attainable, and freedom is worth fighting for,” he says in the video.

“We need the courage to lead and the strength to win.”

Hours earlier, the governor filed paperwork confirming his 2024 bid.

DeSantis decisively won the gubernatorial re-election in Florida last year. In campaign funds and polling numbers, he is the most potent challenger to former President Donald Trump, who has dominated dominates the expanding GOP primary field since announcing his candidacy in November last year.

The other Republican contenders include former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley, business mogul Vivek Ramaswamy, former Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, and Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina. Former Vice President Mike Pence is considering a run.

The choice of the announcement format is novel and representative of DeSantis’s peculiar relationship with the media. The governor has largely walled off establishment outlets in favor of Fox News. Musk has positioned Twitter as the alternative to the establishment news media.

DeSantis scored well in the polls late in 2022 but sank in them early this year as Trump has attacked him relentlessly in social media posts and television ads.

Trump got a boost following his indictment in Manhattan as Republicans rallied around him. Trump racked up endorsements from 11 Florida Congressmen and women, more than half of the state’s Republican delegation.

DeSantis was perceived as stumbling in remarks about the Ukraine-Russia war. Many asked if his candidacy was over before it had even started.

Not having officially declared his candidacy,the governor didn’t formally campaign this spring, although he mounted a book tour amounting to much the same thing.

With DeSantis’s announcement seen as imminent in recent days, though, he’s been buoyed by a steady flow of endorsements: both leaders of Florida’s legislative branches, 99 of 113 Republican legislators, 51 New Hampshire legislators, 37 Iowa legislators.

Georgia Congressman Rich McCormick, a Republican who endorsed DeSantis on May 23 in a statement released by DeSantis’s Never Back Down PAC, said, “This election is not about the past, it’s about the future—who can lift us up? Who can inspire a nation? Who can lead us forward? That’s Gov. Ron DeSantis—a bold conservative, a man of character and conviction, a champion of our values.”

Trump responded to news of the pending annoncement in a series of characteristic messages on his Trump Social media platform. The former president said that DeSantis had backed a nationwide sales tax, sought to “OBLITERATE” social security, and voted to “BADLY WOUND” Medicare.

“Also, he desperately needs a personality transplant and, to the best of my knowledge, they are not medically available yet. A disloyal person!” Trump wrote.

The DeSantis political operation did nor respond to a request for comment.

Rumors of his impending announcement grew as his governor’s office press spokesman, Bryan Griffin, moved to DeSantis’s political operation around May 15. His political staff severed ties with the Florida Republican Party and moved into their own quarters.

And the endorsements began—risky perhaps for the endorsers, going against a former president seen both as the favorite and as vindictive, someone politicians wouldn’t likely cross unless they were certain DeSantis planned to run.

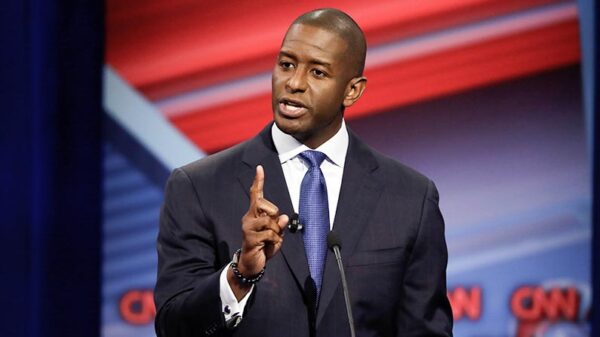

The announcement is the latest development in a remarkable five-year rise to political prominence for DeSantis. In 2018, having resigned from Florida’s 6th Congressional District seat after winning the Republican primary for governor. After an endorsement from Trump he barely squeaked into the governor’s mansion, winning a victory of just over 32,000 votes, .4 percentage points over Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum.

DeSantis often mentions how he won with only 50 percent of the vote but received 100 percent of the executive power. While many in his position would have governed cautiously, DeSantis made bold strokes from the beginning.

Within weeks of his inauguration, he had suspended Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel largely for his response to the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland; he’d signed an executive order calling for the end of the controversial Common Core education curriculum in Florida.

And he appointed three new justices to the Florida Supreme Court, shifting its majority from liberal to conservative.

The governor’s handling of the response to the the COVID-19 outbreak elevated his national profile. DeSantis took longer than most governors to shut down Florida initially, not doing so until April 1, but reversed course in June, saying, “We’re not shutting down. We’re going to go forward. We’re going to continue to protect the most vulnerable.”

While the rest of the nation socially distanced, he reopened the state’s signature beaches. While the rest of the country masked up, he resisted mandates to do the same in Florida. Businesses started reopening in June. All 67 Florida school districts were open for in-school learning by October 2020.

Florida saw some surge in cases due to its more open approach. But its fatality rate, age-adjusted, as of October 2021 was average for the nation, ranked 24th. And its life expectancy, dropping 1.5 years according to CDC statistics in 2020, was less than the national average of 1.8 years.

DeSantis faced criticism from every quarter—the federal government, Democrats more or less unanimously, and even some Republicans. But polls showed Floridians liked what they saw. His approval ratings were as high as 64 percent by February 2021, a year after the pandemic started.

For years a deeply divided battleground state—the one upon which the controversial Bush-Gore election of 2000 hinged, the home of the infamous ‘hanging chads’—its voters returned him to office in November over former U.S. Rep. Charlie Crist by a nearly 10 point margin.

The state’s low crime and unemployment rates, its universities now ranked as the best public system in the nation for its quality and cost, its having no income tax, and other states’ poor performance during the pandemic have all contributed to steady population growth in the state.

DeSantis hammers these points in his frequent press conferences and in his book “The Courage to Be Free: Florida’s Blueprint for America’s Revival,” published in February.

One immigrant to the state is Trump himself, who, while president, switched his official residency from New York to his Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach in November 2019. Trump cited New York’s high taxes and his poor treatment by the city and state leaders in posts on Twitter.

DeSantis’s real signature issue, though, has been his war against wokeness: left-leaning policies advanced through government bureaucracies and increasingly through corporations doing the government’s will and often seeking to control popular thoughts, attitudes, and speech.

COVID-19, with its at-home video schooling, showed more parents what actually went on in their children’s classes in Florida and across the country. Many couldn’t believe what they were hearing.

Countless initiatives led by DeSantis represent the most concerted state-level pushback against the woke agenda. Other Republican-led states echo many of the policies, but few have made it the daily priority that DeSantis has.

The governor’s war against wokeness includes his war with the Disney company and litany of bills he signed into law, including bills addressing culture-war issues like women’s sports, transgenderism, drag shows, critical race theory, and parental rights, among others.

Speaking of environmental and social governance policies on May 2 in Jacksonville, Desantis said, “What this really is, is an attempt by elites to impose ideology through business institutions and financial institutions in our economy, writ large. So they have a vision. This vision is not a vision that usually can win elections around that process. And they want to use economic power to impose this agenda on our society. And we think in Florida, that is not going to fly here.”

DeSantis, 44, was born in Jacksonville in 1978 and grew up in Dunedin, a Tampa Bay suburb north of Clearwater. His father installed Nielsen TV boxes, and his mother was a nurse. He played baseball, and his Dunedin Little League team went to the Little League World Series in 1991. He graduated from Yale University, where he was captain of the baseball team, in 2001, and Harvard Law School in 2005.

While at Harvard, he joined the U.S. Navy, where he served as a legal adviser to SEAL Team One and was later stationed at Guantanamo. He deployed to Iraq in 2007 and served as legal adviser to the SEAL commander in Fallujah.

Returning to the United States, he served as a special assistant U.S. attorney in Florida’s Middle District while still on active duty as a Navy officer. He was elected to Congress in 2012 and served three terms until resigning in 2018 to run for governor.

DeSantis married the former Casey Black, a TV news reporter, in 2009 in a ceremony at Disney World. They have three children, ages 6, 5, and 3. Casey DeSantis is seen as his closest adviser, bringing her communications expertise, and has been a public advocate on issues such as cancer treatment and children’s resilience.

DeSantis mentions his children, and their ages, frequently a public reminder that issues involving children, such as schools, crime, and health care, have personal as well as political value for his wife and him.

Ivan Pentchoukov contributed to this report.