Earlier this year, Jeremy Strong left his apartment in Brooklyn, walked across the bridge to Manhattan and headed towards the far west side of the island, where he was filming the third season of the feverishly adored and heavily accoladed HBO series Succession. Strong plays Kendall, the alternately bullied and rebellious son of the vilified, Murdoch-esque media tycoon Logan Roy, played by Brian Cox, and Succession follows the jostling among the patriarch’s four children for his affection and respect, both of which he generally withholds. None of them is as visibly crushed by this as Kendall, who bears more than a slight resemblance to James Murdoch, even down to the dabblings in hip-hop. With every timid step Strong makes on screen, every apologetic dip of his chin when he starts to talk, he captures the pain of a son who knows he has failed to live up to his father’s expectations from the first time he cried. He won an Emmy last year for the role, beating, among others, Cox, in neatly Freudian style.

Strong likes to walk while learning his lines, so on that day in New York as he was walking he was also talking, reciting a speech he would soon be saying to Cox, in which Kendall tries to curry favour with his father, but also to be seen as his own man. “Suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a ghost-grey Tesla rolling to a stop, so I looked in it, and there was James Murdoch,” Strong says when we meet in a London hotel. “He looked at me and I looked at him, and there was a flicker between us. Then he was gone. So we had a moment.”

Strong has a slight tan and, because he happens to be dressed all in brown (jacket, T-shirt, trousers), he looks a little like a sleek, velvety teddy bear. There is a softness to him, whereas Kendall is all prickles and pain. But even in the telling of this anecdote, Strong takes on Kendall’s tics, the shoulders raising an inch, his voice dropping a half-octave. And then, Kendall-like, he suddenly doubts himself: maybe Murdoch didn’t really recognise him, maybe he doesn’t watch the show. At least one member of the Murdoch family is a fan, I say: last year I interviewed Cox and he said that a man once approached him to say his wife enjoyed Succession but “found it a little hard to watch sometimes”. His wife, Cox revealed with a mighty cackle, was James Murdoch’s sister, Elisabeth.

Unlike Cox, Strong stays serious: “Yes, I heard about that. And of course that means you feel a greater sense of responsibility.” There is a pleasingly apt difference between interviewing the father and the son: where Cox (like Logan) was all devil-may-care swearing, Strong (like Kendall) is quiet and intense. My God, he’s intense. When he arrives, I start by making small talk, asking whether it’s nice to be in London, given he studied at Rada as an 18-year-old. But Strong is not one for casual chat. “It is,” he says. “For me, this city is very connected with the mythology of my life. I slept outside the National Theatre to see Ian Holm play Lear in a Richard Eyre production. It was one of those revelatory things that changed my life and I thought, ‘That’s what I want to do.’ So it feels like a talismanic place.”

Within a few more minutes, he’s quoting acting inspiration he gleaned from TS Eliot’s Four Quartets, Hamlet, Cy Twombly, Chekhov and “Dustin Hoffman quoting Jacques Cousteau – I think about this quote all the time: You have to know how far to go to go too far.” (I think this is actually a version of an Eliot quote: “I do not see how anyone can go very far … who is not ready to risk complete failure.” But who am I to argue with Strong, Hoffman and Cousteau?) “I remember things that are instructive. They are like northern lights for me,” Strong says.

He is eloquent but – initially – self-conscious, although that’s probably because doing interviews makes him anxious. “I always think beforehand: ‘What the fuck am I going to talk about?’” he says. Because of that anxiety, he prepared for this interview the way he prepares for a role: intensely. He researched me and comes ready with questions about my childhood and work. He is especially interested in my recent interview with the author Edward St Aubyn, who was abused by his aristocratic father. It’s not hard to see why Strong-as-Kendall would feel a kinship there: “It was so moving to me that he said he was crushed so easily. That world he inhabits is so redolent of Succession,” he says.

Due to the heightened secrecy around the show, I’m not allowed to see even one episode from the new season, so I’ve no idea what has happened to poor Kendall after we saw him publicly denouncing his father at the end of season two. The only clue Strong gives is to say that he and Succession’s creator, Peep Show’s Jesse Armstrong, talked a lot about F Scott Fitzgerald’s 1936 essay about his breakdown, The Crack-Up. “Jesse said, ‘It’s like winning a grand slam. Has Kendall freed himself? Or has the crisis of getting what he wanted made it worse?’”

Strong doesn’t just think about his character – he fully commits to him. “I feel a great responsibility to understand his pain and feel the weight that’s on him,” he says, and unfortunately for him, there’s a lot of weight on his character. Kendall is so painfully self-destructive that he ended season one attempting to buy drugs and inadvertently causing the death of a young man in the process, and season two cutting himself off from his own family. So it’s hard to imagine that things are going brilliantly for him in season three.

I ask Armstrong if he ever worries that he’s putting too much on Kendall, given how much Strong internalises it: “Honestly, no. When you’re writing, you need a chip of ice in the heart about taking the character to uncomfortable places. But on a friend/human level, I do feel for Jeremy. I remember after he’d been doing gruelling stuff in the second season, he came back to the set one day with his family and I didn’t recognise him for a beat – he was physically transformed, back from this sort of vacancy to a human being with his lights switched back on again, burning.”

They only finished shooting two weeks before we speak, and I ask Strong how long it takes for him to get Kendall out of his system. “I don’t think he does leave me,” he says. “I don’t really feel like an actor much any more; I feel as if I’m me for half the year and I’m Kendall for half the year. I think when you live with a role for long enough, like Mark Rylance playing Rooster in Jerusalem, then it’s in you.”

My tolerance for thespy actor chat is usually pretty low (oh, you think acting is such a profound profession? Allow me to introduce you to brain surgery). But, to my surprise, I enjoy it from Strong, and it takes me a while to figure out why. Finally, as our interview runs on far past our allotted time, I get it: often when actors wax on about how they lived among sheep for a year to play a shepherd, it feels as if they’re stroking their ego, but with Strong, it feels like endearing enthusiasm. Every conversation with him, whatever the subject, whirlpools back to acting, like a person who can’t stop talking about their true love, or a child on their favourite obsession. Also, he has the talents to justify the talk.

Even leaving aside Succession, he has long been making a name for himself as a highly talented character actor, one who started in New York theatre and quickly become a favourite of directors as varied as Kathryn Bigelow (Zero Dark Thirty, Detroit), Adam McKay (The Big Short, as well as the pilot of Succession) and Aaron Sorkin (Molly’s Game, The Trial of the Chicago 7). Does their fondness for him suggest he’s easy to direct? “I don’t think any of those directors would say I’m easy, but they know I put it all on the line,” he says with a wry smile.

“Jeremy takes his work extremely seriously,” says Rafe Spall, who acted with Strong in The Big Short, the adaptation of Michael Lewis’s book about the 2008 financial crisis. “When we were filming the scene when we discover that Bear Stearns has tanked, Jeremy was sitting next to me and I saw he was looking at his phone a lot. I asked what he was looking at and he said, ‘Pictures of plane crashes.’ He told me they put him ‘in the right place’.”

When Sorkin cast him in The Trial of the Chicago 7 as Jerry Rubin, the countercultural activist, Strong prepared by “taking all these gummies [edible cannabis], going to Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago and listening to the Grateful Dead. It was a palate cleanser after Kendall.” During the courtroom scene, in which Rubin, fellow activist Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and others were accused of crossing state lines to incite anti-Vietnam riots, Strong, in the spirit of Rubin, brought an “assortment of period noisemakers” to disrupt proceedings. After Sorkin irritably asked him to please stop clanging his cowbell, he slipped a fart machine on the chair of Judge Julius Hoffman, played by Frank Langella, who was less than amused when he sat on it.

“I felt, this is guerrilla theatre and that’s what these guys would do. But Sacha turned to me and said, ‘You can’t do that!’ I was like, ‘Dude! You’re Sacha Baron Cohen!’” And it did the trick: the take in which Langella sat on the fart machine, and then glares at Hoffman and Rubin, is the take that appears in the movie.

When he’s making Succession, Strong largely stays separate from the other cast members to maintain the dynamic of the show in which Kendall is emotionally disconnected from his family. “It’s not like I stay in character, but you need to believe in what you’re doing and take it seriously. I don’t know how you can do that without going all out. Also, for me, the creative self and social self are entirely separate. I have a lot of armour and anxieties in my social self, and I have to strip all that away to engage my creative self,” he says.

The relationship between Kendall and Logan is at the heart of Succession and the moments when Logan blows up at his son are almost unwatchably painful. Is it scary to get a Brian Cox gale force 10? “Sometimes. I don’t always know when he’s going to shout at me,” he says, eyes widening. Once, he burst into tears.

I ask if it’s hard for him to maintain a distance from Cox off camera, given how friendly he is in real life.

“Yeah, it is hard, because Brian is so avuncular,” he says, enjoying the word. “We have very different processes, and he tolerates me and I have inestimable respect for him. But I prefer to keep him in his corner and I stay in mine so we can meet in the ring. It harms my sense of the dynamic when it’s so frictionless and warm between us. That bonhomie doesn’t serve the work.”

In season two, in a typical moment of poor judgment, Kendall performed an unforgettably weird rap for his father to show him his love, much to Logan’s displeasure. Wasn’t Strong tempted to laugh in Cox’s face as he said lines like “L to the OG, Dude be the OG”? Strong recoils, shocked: clearly I still don’t get it.

“Oh no! Laughter isn’t even on the cards – it couldn’t be! Because the rap was sincere, it’s committed. I don’t feel as if I’m doing a scene for Brian Cox, I feel as if I’m rapping for my dad,” he says.

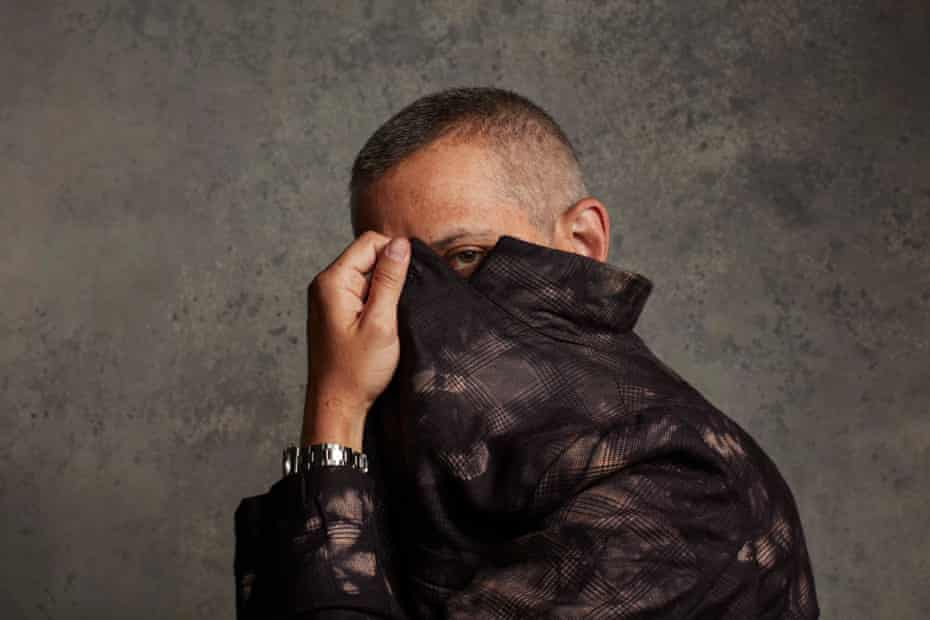

I ask if he can do the rap for me and he says no. “It’s not a parlour trick,” he says, a gentle rebuke. “But there was something wonderful about doing the rap, because it was expressive and not internal. So much of the time there’s a muzzled anguish that lives in Kendall. But when he convinces himself he’s free, it’s a real reprieve because he’s not sitting in the burning chair any more.” Strong often makes viscerally visual references to describe Kendall’s pain: for the photoshoot, his suggestions included him appearing to be on the verge of drowning, and burning his script (the latter was safer).

It is Strong’s natural intensity – that ability to sit in the burning chair – that makes him feel so perfectly cast as Kendall, says Armstrong: “I normally think I prize doubleness or the ability to do two things at once. Of course, Jeremy can do that and play, say, confidence which is both undermined by a deeper lack of confidence, but also bolstered and pumped up by a need to act out the confidence which is a mask. But what he brings is what I prize most highly, and that’s single-mindedness. He finds these absolute convictions in the character, and in a world that is full of all kinds of phoniness, Jeremy-as-Kendall’s singularity of wanting is very important. Even if what Kendall wants is in some ways bullshit, his wanting is very pure. And when we see the strings cut on that wanting, and he’s left flailing without a purpose, that’s very affecting, too.”

Armstrong has always insisted the show is not based on the Murdochs. “Or the Trumps, or the Sulzbergers, or the Newhouses, or any of those dynastic media families,” Strong adds (although he did read everything he could about James Murdoch when he got the part, and yes, he does see the many resemblances between Kendall and Donald Trump Jr). Yet he has a habit of appearing in films that are based on actual events. As well as the Bigelow, Sorkin and McKay films, he played Lee Harvey Oswald in Parkland. He was especially good in The Big Short, playing a compulsively gum-chewing investor who quickly grasps the scale of what’s coming. “I’ve always been drawn to stories about the times we live in, and when Adam McKay came to me with Succession, it felt very much like what he did with The Big Short and Vice [about Dick Cheney]. He’s made this triptych of American life,” he says. Yet by signing up for the show, Strong upended what he expected for his own life: “I thought I would always be one of those chameleonic character actors. But with Jesse’s writing, there’s something more naked being asked of me. There’s nowhere to hide. Kendall’s rage, his pain, his contempt, his shame, his feelings of inadequacy – all of those things are mine. And that feels very different from just putting on a funny voice when you’re a kid.”

Strong was born and raised in Boston. His mother was a hospice nurse and his father works in juvenile justice, “so I couldn’t have been further away from the world of Succession”. As a child, he says, “I never felt able to take up space in the room.” But when he was on stage, he was liberated: “It was just this abracadabra where you’re free from your inhibitions, the way you’re perceived by others and even the way you perceive yourself. I think acting, for me, was a way to disappear from my normal social self and also a way to appear more forcefully. Honestly, I don’t know what I’d do without acting.”

He started doing plays at school, encouraged by his English teachers, and when he was 18, he was accepted on a Rada summer course. He read Laurence Olivier’s autobiography and fell in love with his descriptions of “theatrical courage” and being bold in one’s performance: “That English tradition in acting which we don’t have as much in America, even in film,” he says. After graduating from Yale, where he majored in English, he scratched out a living in New York, getting whatever jobs he could in theatre. When he was in his mid-20s, he was hired as Daniel Day-Lewis’s assistant on the set of 2005’s The Ballad of Jack and Rose. I ask if it was Day‑Lewis – famously no slouch when it comes to immersing himself in a role – who encouraged him to take his fully committed approach to acting.

“I had always had a predilection towards that, but seeing the level of Daniel’s commitment, his courageousness, his willingness to make a fool of himself – that had a profound and formative effect on me,” he says.

What was he doing for Day-Lewis as his assistant? “Oh, just mundane stuff.” Like getting his coffee? Strong is amused at the thought: “No, he’s not someone who needs anyone to get him coffee.” I start to ask again, but he stops me: “I feel very protective of his privacy.” Whatever it was, Strong obviously did such a convincing job of being Day-Lewis’s assistant that he was cast as his private secretary in Lincoln – another role based on a real person. Surely they had a laugh about that?

“No, no. Maybe afterwards, but getting that part was so meaningful to me. Although I didn’t do much in that movie and, as an actor, you want to go at 200mph – you want to be playing Lincoln!” he smiles.

Quick Guide

Saturday magazine

Show

This article comes from Saturday, the new print magazine from the Guardian which combines the best features, culture, lifestyle and travel writing in one beautiful package. Available now in the UK and ROI.

In 2006, Strong was in a tiny play that was “as far off Broadway as you can get without being in the river”. Philip Seymour Hoffman, along with the Pulitzer prize-winning playwright John Patrick Shanley, happened to see his performance. On the back of that, Shanley cast him in his play Defiance, and that led to his first film role, as the lead in the indie movie Humboldt County in 2008. Did he stay in touch with Hoffman?

“Not that closely, but the New York theatre world is pretty small so I’d see him around and he was always very kind to me. I remember when I was in rehearsals for Turgenev’s A Month in the Country and I was talking to Phil about my difficulties with it, he told me to ‘Err on the side of going for it.’ When I think about him, I think about that, his boldness, his … ” He trails off, his eyes filled with tears. Hoffman died of a drug overdose in 2014, at the age of 46. I apologise for bringing up something so sad. “No no, it’s just – he was a hero to all of us,” he says.

We move on to happier subjects, namely, his wife, Emma Wall, a psychiatrist, whom he never mentions without smiling. The two met at a party in New York in 2012, while Hurricane Sandy raged outside. They married in 2016 and live mainly in New York, but have a home in Copenhagen, and Strong proudly shows me the Danish labels on his clothes. “I love Denmark. I find it a very sane and gentle place. It feels like a refuge for me, and it’s great to have somewhere that’s a docking station after all this work, which I find very enervating and scary and stressful,” he says. I ask if his love for Hamlet motivated him to buy a home in Copenhagen. He laughs and says no, it’s because his wife is half-Danish, but adds: “I’ve always wanted to play Hamlet, and I may not get to, but I feel he’s embedded in Kendall, that thwarted will and inability to take action.” He has, of course, visited Helsingør: “Shakespeare never saw it, but you like to think, ‘There’s Hamlet’s castle,’” he says wistfully.

Strong and his wife have daughters aged three, 18 months, and another born just after our interview. “So three sisters,” he smiles. He has created a Chekhovian family while living in Copenhagen like a Danish prince. I ask how his Danish is and he admits it’s pretty bad. “The truth is – and my wife knows this, so it’s OK for me to say, I think – I have an almost pathological lack of curiosity about most things. But when it comes to work, I’m inexhaustible. So if I had to learn Danish for a part, I would.”

I ask him if it’s possible that he does too much for his work. Does he really have to take on all of a drug addict’s pain to play a drug addict?

“There have been times when it has felt really hard, but if the character is going through an ordeal, and you want the audience to experience that, then you can’t spare yourself. I have a belief – and this may be a fallacious belief – that it has to cost you something,” he says. Then he adds something that could be both Kendall’s personal mantra and a description of Strong’s work ethic: “I need it to be difficult.”