MSNBC’s top-rated host Rachel Maddow devoted a segment in 2019 to accusing the right-wing cable outlet One America News (OAN) of being a paid propaganda outlet for the Kremlin. Discussing a Daily Beast article which noted that one OAN reporter was a “Russian national” who was simultaneously writing copy for the Russian-owned outlet Sputnik on a freelance contract, Maddow escalated the allegation greatly into a broad claim about OAN’s real identity and purpose: “in this case,” she announced, “the most obsequiously pro-Trump right wing news outlet in America really literally is paid Russian propaganda.”

In response, OAN sued Maddow, MSNBC, and its parent corporation Comcast, Inc. for defamation, alleging that it was demonstrably false that the network, in Maddow’s words, “literally is paid Russian propaganda.” In an oddly overlooked ruling, an Obama-appointed federal judge, Cynthia Bashant, dismissed the lawsuit on the ground that even Maddow’s own audience understands that her show consists of exaggeration, hyperbole, and pure opinion, and therefore would not assume that such outlandish accusations are factually true even when she uses the language of certainty and truth when presenting them (“literally is paid Russian propaganda”).

In concluding that Maddow’s statement would be understood even by her own viewers as non-factual, the judge emphasized that what Maddow does in general is not present news but rather hyperbole and exploitation of actual news to serve her liberal activism:

On one hand, a viewer who watches news channels tunes in for facts and the goings-on of the world. MSNBC indeed produces news, but this point must be juxtaposed with the fact that Maddow made the allegedly defamatory statement on her own talk show news segment where she is invited and encouraged to share her opinions with her viewers. Maddow does not keep her political views a secret, and therefore, audiences could expect her to use subjective language that comports with her political opinions.

Thus, Maddow’s show is different than a typical news segment where anchors inform viewers about the daily news. The point of Maddow’s show is for her to provide the news but also to offer her opinions as to that news. Therefore, the Court finds that the medium of the alleged defamatory statement makes it more likely that a reasonable viewer would not conclude that the contested statement implies an assertion of objective fact.

The judge’s observations about the specific segment at issue — in which Maddow accused a competitor of being “literally paid Russian propaganda” — was even more damning. Maddow’s own viewers, ruled the court, not only expect but desire that she will not provide the news in factual form but will exaggerate and even distort reality in order to shape her opinion-driven analysis (emphasis added):

Viewers expect her to do so, as it is indeed her show, and viewers watch the segment with the understanding that it will contain Maddow’s “personal and subjective views” about the news. See id. Thus, the Court finds that as a part of the totality of the circumstances, the broad context weighs in favor of a finding that the alleged defamatory statement is Maddow’s opinion and exaggeration of the Daily Beast article, and that reasonable viewers would not take the statement as factual. . . .

Here, Maddow had inserted her own colorful commentary into and throughout the segment, laughing, expressing her dismay (i.e., saying “I mean, what?”) and calling the segment a “sparkly story” and one we must “take in stride.” For her to exaggerate the facts and call OAN Russian propaganda was consistent with her tone up to that point, and the Court finds a reasonable viewer would not take the statement as factual given this context. The context of Maddow’s statement shows reasonable viewers would consider the contested statement to be her opinion. A reasonable viewer would not actually think OAN is paid Russian propaganda, instead, he or she would follow the facts of the Daily Beast article; that OAN and Sputnik share a reporter and both pay this reporter to write articles. Anything beyond this is Maddow’s opinion or her exaggeration of the facts.

In sum, ruled the court, Rachel Maddow is among those “speakers whose statements cannot reasonably be interpreted as allegations of fact.” Despite Maddow’s use of the word “literally” to accuse OAN of being a “paid Russian propaganda” outlet, the court dismissed the lawsuit on the ground that, given Maddow’s conduct and her audience’s awareness of who she is and what she does, “the Court finds that the contested statement is an opinion that cannot serve as the basis for a defamation claim.”

What makes this particularly notable and ironic is that a similar argument was made a year later by lawyers for Fox News when defending a segment that appeared on the program of its highest-rated program, Tucker Carlson Tonight. That was part of a lawsuit brought by the former model Karen McDougal, who claimed Carlson slandered her by saying she “extorted” former President Trump by demanding payments in exchange for her silence about an extramarital affair she claimed to have with him.

McDougal’s lawsuit was dismissed in September, 2020, by Trump-appointed judge Mary Kay Vyskocil, based on arguments made by Fox’s lawyers that were virtually identical to those made by MSNBC’s lawyers when defending Maddow. In particular, the court accepted Fox’s arguments that when Carlson used the word “extortion,” he meant it in a colloquial and dramatic sense, and that his viewers would have understood that he was not literally accusing her of a crime but rather offering his own subjective characterizations and opinions, particularly since viewers understand that Carlson offers political commentary:

Fox News first argues that, viewed in context, Mr. Carlson cannot be understood to have been stating facts, but instead that he was delivering an opinion using hyperbole for effect. See Def. Br. at 12-15. Fox News cites to a litany of cases which hold that accusing a person of “extortion” or “blackmail” simply is “rhetorical hyperbole,” incapable of being defamatory. . . .

In particular, accusations of “extortion,” “blackmail,” and related crimes, such as the statements Mr. Carlson made here, are often construed as merely rhetorical hyperbole when they are not accompanied by additional specifics of the actions purportedly constituting the crime. . . . Such accusations of crimes also are unlikely to be defamatory when, as here, they are made in connection with debates on a matter of public or political importance. . . . The context in which the offending statements were made here make it abundantly clear that Mr. Carlson was not accusing Ms. McDougal of actually committing a crime. As a result, his statements are not actionable.

When discussing Carlson’s show generally and how viewers understand it, the court used language extremely similar to that invoked to protect Maddow from defamation lawsuits: namely, that Fox viewers understand that Carlson is, in addition to presenting news, offering his own subjective analysis of it:

In light of this precedent and the context of “Tucker Carlson Tonight,” the Court finds that Mr. Carlson’s invocation of “extortion” against Ms. McDougal is nonactionable hyperbole, intended to frame the debate in the guest commentator segment that followed Mr. Carlson’s soliloquy. As Defendant notes, Mr. Carlson himself aims to “challenge[] political correctness and media bias.” Def. Br. at 14. This “general tenor” of the show should then inform a viewer that he is not “stating actual facts” about the topics he discusses and is instead engaging in “exaggeration” and “non-literal commentary.”

Fox News has convincingly argued that Mr. Carlson was motivated to speak about a timely political cause and that, in this context, it is clear that his charge of “extortion” should not be interpreted as an accusation of an actual crime. Plaintiff’s interpretation of Mr. Carlson’s accusations is strained and, the Court finds, not reasonable when the entire segment is viewed in context. It is true that Mr. Carlson added color to his unsubstantiated rhetorical claim of extortion when he narrated that Ms. McDougal “approached” Mr. Trump and threatened his career and family. See Am. Compl. ¶ 10. But this overheated rhetoric is precisely the kind of pitched commentary that one expects when tuning in to talk shows like Tucker Carlson Tonight, with pundits debating the latest political controversies.

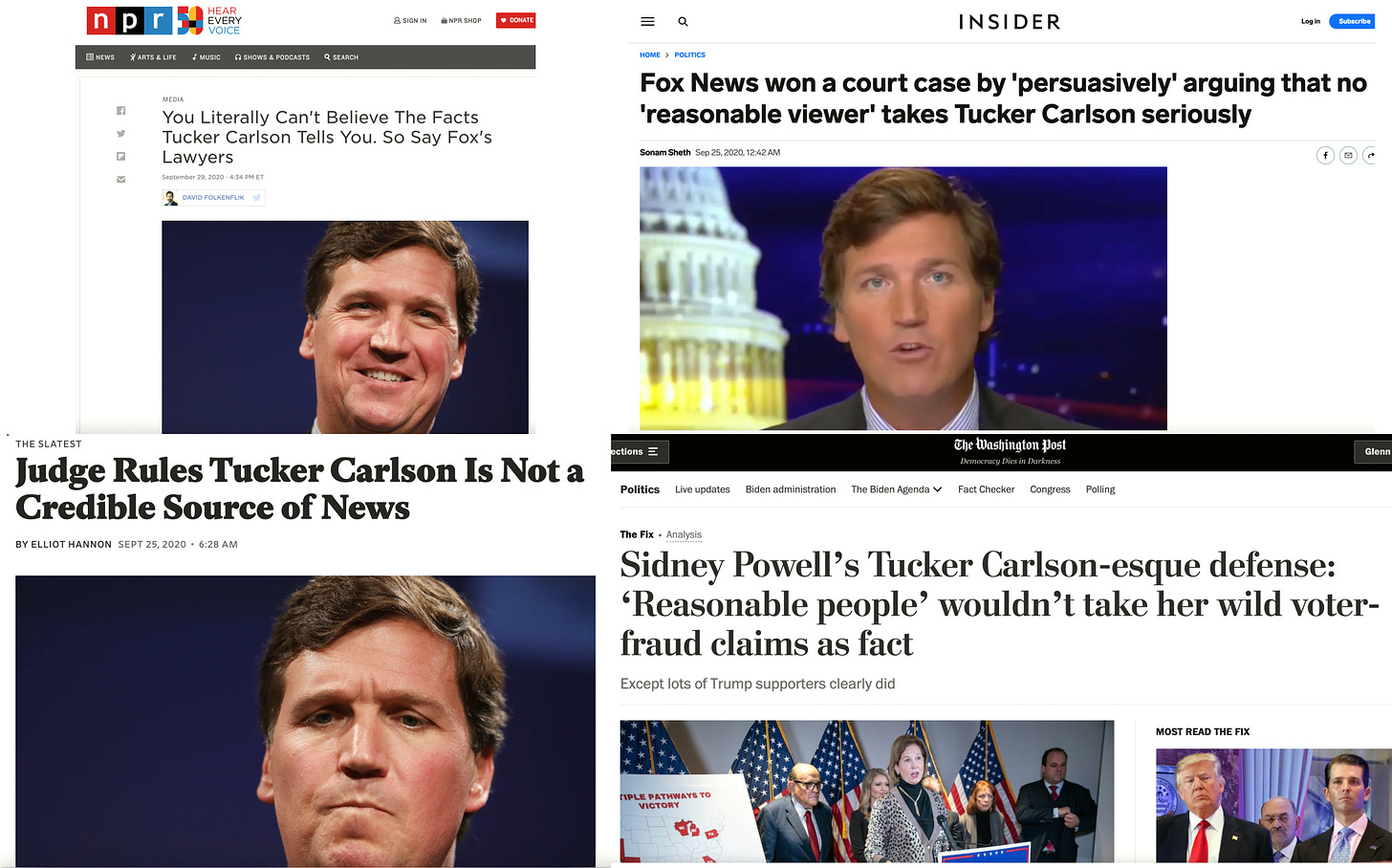

This is worth noting because of how often, and how dishonestly, this court case regarding Carlson is cited to claim that even Fox itself admits that its host is a liar who cannot be trusted. This court ruling has become a very common argument used by liberals to claim that even Fox acknowledges that Carlson lies. Indeed, Maddow’s own colleague Chris Hayes — whose MSNBC program is broadcast at the same time as Carlson’s and routinely attracts less than 1/3 of the Fox host’s audience — has repeatedly cited this court case to argue that even Fox admits Carlson is a liar, without bothering to note that his companies’ lawyers made exactly the same claims about his mentor, Rachel Maddow, to defend her from a defamation lawsuit:

This claim — even Fox admits that Carlson is a liar who cannot be believed! — has become such a common trope among liberals that it is impossible to count how many times I have heard it. And that is because the liberal sector of the corporate media blared this claim in headlines over and over after the lawsuit against Fox was dismissed.

It is virtually impossible to find similar headlines about Maddow even though the judicial rationale justifying dismissal of the lawsuit against her was virtually identical to the one used in Carlson’s case. Indeed, lawyers for MSNBC and Fox cited most of the same legal precedent to defend their stars and to insist that their statements could not be actionable as defamation because viewers understood it as opinion rather than fact.

I personally agree with the rationale cited in both cases: it becomes dangerous when defamation claims are used to punish or otherwise forbid the expression of political opinion. And of course it is the job of lawyers to mount every possible argument when defending a client, which is why both MSNBC and Fox’s lawyers essentially insisted that viewers of these programs understand that they are not being presented with objective truth and neutral news but political and subjective commentary. That is what made these widespread attempts to weaponize the ruling in Carlson’s case so preposterous.

Indeed, it was Maddow’s statement — that OAN is “literally paid Russian propaganda”— that seems far more actionable than Carlson’s obviously figurative assertion that McDougal was “extorting” Trump. Falsely accusing people of being paid Kremlin agents has a long and ugly history in the U.S., having destroyed reputations and careers, yet this smear has once again become utterly commonplace in Democratic Party politics (a protracted and ugly feud among liberal commentators was initiated earlier this month when The Young Turks’ Cenk Uygur baselessly and falsely claimed that journalist Aaron Maté was “paid by the Russians”).

But whatever else is true, those who want to claim that this court ruling proves Carlson is a lying propagandist who cannot be trusted have no way out of applying the same claim to Maddow. In both cases, it would be unfair and irrational to use these court rulings to suggest that, given that the arguments made were standard ones lawyers advance to defend a defamation defendant. Ironically, those most guilty of being unreliable liars and propagandists are those in the media and even Maddow’s own MSNBC colleagues who repeatedly cite this court ruling to delegitimize Carlson without ever mentioning that Maddow’s lawyers successfully used the same arguments in her defense.

To support the independent journalism we are doing here, please subscribe and/or obtain a gift subscription for others: